“In a universe where impersonal matter endured forever but the personal self was extinguished at death, the most which could survive of that self was a rumor, a reputation. For this, the person craving immortality — a condition proper only to the gods and antithetical to human existence — was totally reliant on poets and poetry.” (Bruce Lincoln, 1991)

— — -

Sidhu Moose Wala’s brief life has left an indelible mark on Punjabi culture, and will measure up to the storied legends that dot Punjab’s cultural landscape, holding its own among the hallowed tales of Jatt Jeona Morh, Sucha Soorma, Heer-Ranjha, Chamkila: rebels, fighters, star-crossed lovers, artists.

Much like Bhagat Singh and Sant Bhindranwale (the two most recognizable icons in modern-day Punjab), Sidhu will become a symbol, more than the sum of his life; an icon, a window that opens up and conveys core attitudes and values of Punjabi culture.

— — -

Sidhu’s aggressive, unapologetic persona was too big to be captured and appropriated by liberal and nationalist idioms regarding Sikhs. His effortless synthesis of rustic folk motifs and gangsta rap aesthetic was only exceeded by his undeniable talent with voice and words. His music seamlessly blended gangsterism, Punjabi folk culture, a ‘rustic’ (deemed “regressive,” “toxic” by the soft-bellied commentariat of the metropoles) sensibility, unabashed masculinity, and on occasion politics.

He chose to eschew the routine props of girls, drugs and alcohol in his music videos, instead cultivating an exhilarating universe of guns, bravado, the ‘crew’ (the männerbund), anakh, enemies and death constantly around the corner — a more thoroughly Jatt set of motifs cannot be put together, all filtered through the aesthetic language of hardcore gangsta rap, and later UK drill.

The image he built also thoroughly shattered the usual portrayals of sardars in popular media (either derisive, bumbling and over the top, or entirely informed by a unidimensional patriotism). He stormed into the limelight as an aggressive, simultaneously ‘pendu’ and urbane sardar, closer to the characters played by Shera in his heyday in the 80s than anything else. Videos of him onstage, imploring his fans to embrace their Sikh heritage, also underlined the pride he took in his roots, refusing to whitewash it or water it down. The masses ate it all up.

To the discerning ear, the poeticisms that Sidhu weaved through his lyrics, subtle at times, sometimes pronounced, betraying a distinctly literary bent of mind, also made it clear that we were witnessing the maturation of a generational talent, operating at a level far beyond the rest.

— — -

Sidhu Moose Wala was murdered during a drive-by shooting while driving his Thar jeep on May 29. Accosted by hitmen armed with automatics, trapped in his vehicle, reports suggest Sidhu nevertheless pulled out his pistol and fired back, emptying his magazine. Thirty rounds were fired at Sidhu, and he eventually succumbed to the grievous injuries.

Sidhu’s death recalls the killing of his idol, the American rapper Tupac, who was similarly gunned down in 1996. Sidhu’s songs are replete with a fatalistic acceptance of death, an infatuation with it. Death is always on the horizon, in the rearview mirror, chasing the man who chases the world, like Nietzsche’s monster promising you that your life is meant to recur eternally (what is time but a procession towards death?).

The songs reveal a man who did not fear death — indeed, he welcomed it, embraced it, oriented his entire being towards attaining a heroic death. The fact that Sidhu’s death affirmed his idealization of Tupac and his own poetic orientation towards death in such a devastating way — one is hard-pressed to deny the workings of a higher power, one that assigns and awards fame, honor, and most importantly, death. Whatever the power, it was surely pleased with Sidhu, and awarded him a death that equaled (and fulfilled) his poetic and reckless ruminations on death.

— —

The logic of folk religion allows for the divinization and apotheosis of worthy men, becoming objects of reverence and worship to the popular mind, intermediaries between God and his devotees. Sidhu’s funeral saw an extraordinary outpouring of emotions as tens of thousands accompanied his parents. Media reports show fans and fellow villagers prostrate before his funeral pyre. This conveys in poignant terms the deep respect the masses held towards him, and how, for those who were present, death transformed this respect into reverence.

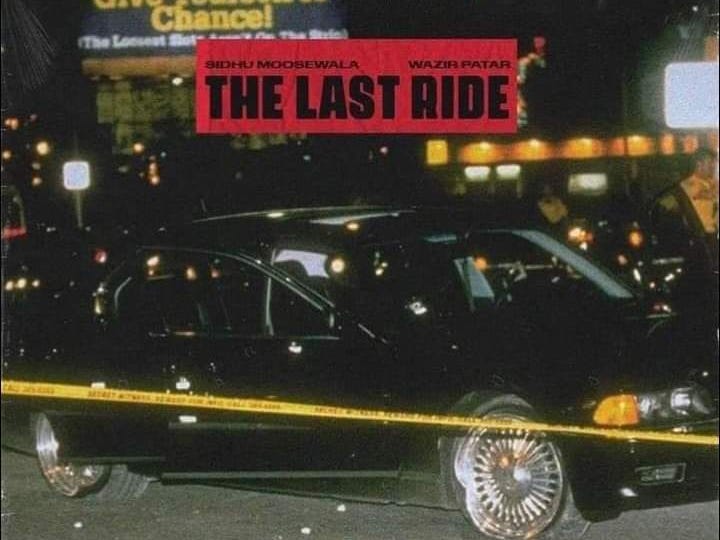

Meanwhile, fans online were quick to note how eeriely accurately his lyrics predicted his own death — one of his last songs, ‘The Last Ride,’ featured Tupac’s car on the cover art, and the chorus exclaimed that the noor (splendor, light) on Sidhu’s face confirmed that his funeral procession was meant to happen in his youth.

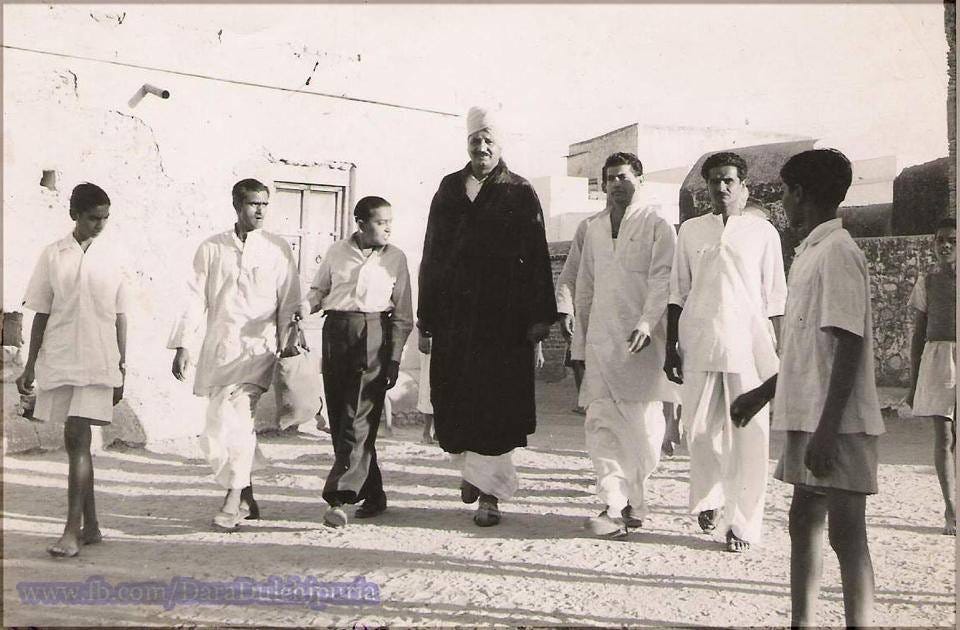

Something less remarked upon (but no less striking) is his uncanny resemblance to the pahalwan Dara Singh Dulchipuriya. A 6'5", physically imposing wrestler, he was briefly imprisoned for avenging his brother’s death, killing three men with his bare hands. Beyond the physical resemblance and similar rustic origins, the violence that visited their lives is another parallel between the two. There is nothing new under the sun, just eternally recurring archetypes and sublime moments that exceed the bounds of our mundane world.

These coincidences certainly add to the myth of Sidhu Moose Wala, and will undoubtedly find themselves the subject of many conversations. This is the stuff that legends and myths are made of, after all.

— — -

Just like the archetypal Jatt rebel, the Indo-European hero rejects the long uneventful life of sedentary civilization in favor of glory, war and fame, encapsulated by the formula ‘ḱlewos ndʰgʷʰitom’ — “fame that does not decay.” Immortality, “a condition proper only to the gods and antithetical to human existence,” lies in achieving eternal greatness, in being remembered, in your fame traveling far and wide, lasting through the crumbling textures of Time. Sidhu’s death ensured his legend will live up to the incommensurable fame he aimed for (but never coveted cravenly) in his songs.

Sidhu’s cavalier, almost playful disdain towards death might have offended bourgeois sensibilities, rooted as they are in the logic of utility and self-preservation, but the archaic warrior would have found a worthy kin in Sidhu.

And in dying in a hail of gunfire, emptying his own pistol in defence, he emulated and indeed overtook his idol Tupac. He died like a man, a mard, an “ankhi Jatt,” living up to his poetic longing for a heroic death. His death sealed his legend, granted him immortality: driven by the Will, it overcame the profane, mundane bounds of the samsara and attained the sublime. Mishima would applaud.

Beautiful, no words to write about it

Dhillon, feem khani shadh tu hun jaada kuch kar reha