“The need to go astray, to be destroyed, is an extremely private, distant, passionate, turbulent truth.” (Georges Bataille, 1944)

“Through its instability and destructiveness the warrior’s world called forth its own destruction.” (Jan Heesterman, 1989)

— — -

bhagat bhagautī sāj kai

ਭਗਤ ਭਗਉਤੀ ਸਾਜ ਕੈ ਪ੍ਰਭੁ ਜਗ ਅਰੰਭ ਰਚਾਇ ਹੈ ॥—After creating the divine (devoted) Bhagauti, God began the task of creation of the world. As one of the fundamental principles of Sikh metaphysics, the term ‘Bhagauti’ is pregnant with a polysemic multiplicity of meanings, simultaneously translatable as the Devi, as the sword, as power, as Maya, as God’s divine potency (ਕਾਲ ਕੀ ਕਲਾ—the kalaa of Kaal), as creative faculty, as potentiality, as magic, as technics, and so on. Pintchman (1994) identifies prakrti, shakti and maya as the ‘symbolic complex’ of the Great Goddess.

The various goddesses, in turn, are totemic representations of various aspects of the same Devi’s limitless, primordial power. Vahiria writes, ਸੋ ਮਾਇਆ ਕਹੋ ਦੇਵੀ ਕਹੋ ਭਗਵਤੀ ਕਹੋ ਭਵਾਨੀ ਕਹੋ ਸਕਤੀ ਕਹੋ ਸਭ ਇਕੋ ਵਸਤੁ ਦੇ ਨਾਮ ਹਨ ॥—[One may address her] as Maya, as Devee, as Bhagavatee, as Bhavanee, as Shaktee; these are all names of the same substance.

— — -

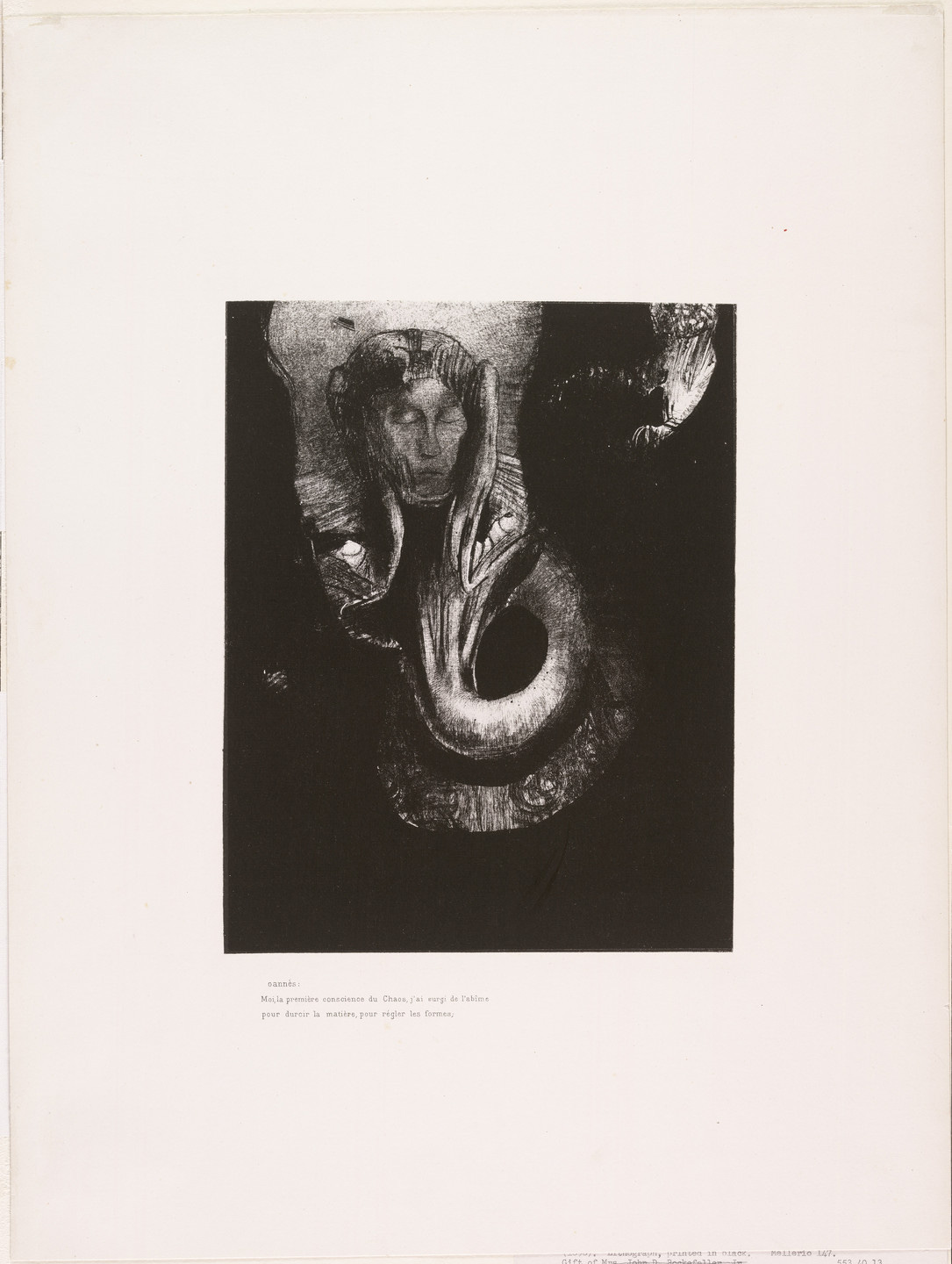

In her most apocalyptic aspect, Bhagauti adopts the guise of Kalika: the ferocious, terrifying, sublime harbinger of destruction, the oppressive gravity of death and time, the cosmic spirit of war. Kalika is present on every battlefield, exulting in the turbulent, sonorous tonalities of battle. War is her sacrificial rite, the battlefield her altar. Conjured by the frenzied heat of war, the Devi’s transactional economy demands blood and martyrdom, bestowing glory and immortality.

Kalika’s wrath reveals itself in all its frightening glory in the kshatriya’s apocalyptic principle of total war, as an all-devouring, expanding, libidinal, chaotic vortex of war. It seeks to reach the highest tonality, to dissipate itself in ruinous dépense. At its apotheosis its vigorous currents threaten to obliterate all gregarious frameworks, luxuriating without a goal in the pure, escalating, sublime excess of aktionismus, heralding the destruction of the very cosmos it engenders and upholds. It is driven by “not self-preservation, but the will to appropriate, dominate, increase, grow stronger” (Nietzsche) in a state of joyous, sovereign excess. ਨਮੋ ਰਿਸਟਣੀ ਪੁਸਟਣੀ ਪਰਮ ਜੁਆਲਾ ॥—Salutations [to the Devi] the healthiest, most vigorous, the supreme form of fire.

Of course, within this mortal realm we inhabit, with its limits to growth and finite resources, this self-destructive vortex, once unshackled, ends up devouring its conjurers, its finest practitioners— sacrificial offerings to the Devi’s general economy.

— — -

Witnessing the flogging of the Turin horse, Klossowski’s Nietzsche experienced an ecstatic break from the despotic apparatus of the social gregarious self— leaping into the ‘incoherence of the impulses’, ‘intensity of forces’— a lucid, rich, vigorous plurality of intensities (devoured by the Devi). Heraclitus speaks of an ‘ever-living fire, being kindled in measures and being put out in measures.’ Bataille evokes ‘a primal continuity linking us with everything that is,’ one we are severed from in life and attempt to access in moments of sovereign excess.

This freely expending, overflowing chaos of intensities is essentially the same as the kshatriya’s principle of the self-devouring vortex of war that the framework of ‘the Self, the World and God— the three terminal points of traditional metaphysics’ necessarily tempers and stabilizes.

— — -

Taking this aspect of Bhagauti as the all-consuming vortex of war, the universe is understood to be conceived in the wealth of chaos, of euphoric, relentless, annihilative violence. Vahiria calls the Devi -੦-, ਸੁੰਨ (sunn), बिंदु (bindu), صفر (sifr)— void, absence, negation. Najm Kobra’s black light, nur e-siyaah. Night of light, luminous Blackness.

From the cosmogonic womb of this void emerges the formless violence of multiplicity, of intensities and drives, of phenomenal flux and churn, which must then be conquered and mastered via chaoskampf. This is the essence of dharam, and of dharam-yuddha, within and without.

— — -

The principle of conflict

The Vedic’s warrior’s world was one of amhas, of scarcity and dire need. He who sought to conquer the goods of life had to resort to violence, and so conflict and violence fulfilled a ‘market function’ insofar as they governed exchange and distribution.

But this equally means that violent conflict is not an aberration, a matter of competition getting out of hand, but the pivotal dynamic principle. It is this principle that is celebrated as the cosmogonic theme of the relentless war between devas and asuras.

“For him—the raajanya, the royal warrior—there is no compromise, either he conquers or he is conquered.” Wandering the wilderness, raiding enemy settlements, fending off rivals, competing in agonistic sacrifices, the warrior was oriented towards death; he walked in its shadow, born into it.

As a victor, the raajanya sought to rise from an itinerant raider, a knight-errant of sorts, to the munificent magnate, a bestower of gifts, bounty and offerings— the ceremonial, circulating economy of sacrifice.

— — -

The archaic warrior’s order was thus an endangered one: between alternating cycles of peaceful, settled community and the violent transhumance of raiding expeditions, he risked his life to stake his claim on the goods of life and to vindicate himself as the fundamental connective force that held together the ambiguous gulf between life and death, order and disorder— the rajan’s enigmatic sacrality (the king’s divine body).

Crisis was the ‘very center and foundation’ of this world, tension, uncertainty and instability its driving principles. The warrior was constantly haunted the possibility of disasters and reversals, of ‘violent catastrophe.’ The only principle that guaranteed the rules of conflict was conflict itself.

ਸਿੰਘਨ ਪੰਥ ਦੰਗੈ ਕੋ ਭਇਓ।—The order of the Singhs was created for dangaa; ਦੰਗਾ—dangaa being the operative word, signaling riot, chaos, war, destruction.

The warrior is the one who finds comfort only in being strong, not only in the face of this or that adversary, in this or that situation, but strong absolutely, the strongest of all. … And above all, dedicated to Force, they are the triumphant victims of the internal logic of Force, which proves itself only by surpassing boundaries— even its own boundaries and those of its raison d’etre.

The Nietzschean pursuit of ‘a maximal feeling of power; essentially a striving for more power’ compelled the warriors to play this game of death. And so it was that, in this vortex of instability, stability and longevity were eschewed in favor of glory and ‘the goods of life’: ḱlewos ndʰgʷʰitom ‘fame that does not decay’ and गविष ‘desire or eagerness for cows’— the fundamental tenets of the Indo-European warrior’s worldview.

This is the cold, tragic heart of the warrior’s destiny: he must perish in the vertiginous vortex of conflict.

— — -

The sacrificial cycle of violence collapsed under the strain of its own unbearable tension and was replaced by the perfect order of ritualism… [Vedic ritualists] constructed out of the dismembered elements of the organic sacrificial world the mechanistically ordered and systematized world of ritual which… only requires the risk-free knowledge of ritual.

To stave off collapse, the bloody, unstable order of the warrior was replaced at the center of the archaic world by the stability of the priest’s order. Thus the dual poles of sovereignty— the magician-king and the jurist-priest— settled in an internal stratum of the brahma guiding the kshatra, the sacerdotium commanding the regnum. The priestly orthodoxy replaced the ‘drama of violent confrontation’ with the ‘certainty and static stability of ritual.’ The sacred, in turn, was transfigured from a bloody, magical, ecstatic affair to the ordered, stable world of ritual and transcendence. The sacred was now closed to the uncertainty of conflict and contest.

Speaking of scriptural injunctions against sacrifices like the ashwamedha in kaliyuga, Heesterman writes, “men of our era are no longer deemed strong enough to cope with the heady excitement and terror of sacrifice.” Somewhat ironically, the Purusha Sukta (Rigveda 10.90) presents a cosmogony rooted in sacrifice. In sacrificing and dismembering the primeval man, the gods transform the “unchecked expansiveness of his vitality and turn it into the articulated order of the universe and life.” Order itself emerges from sacrifice, life from death: the enigmatic oppositions fold into one another. Sacrificial violence engenders (nurtures, nourishes) the cosmos.

In ensuring a sustainable and lasting cosmos, the orthodoxy eliminated the possibility of experiencing as sacred the vigorous, frenzied ecstasy of sublime excess and bloody spectacle that soaked the ever-fracturing world of the archaic warrior. “Death and violence were taken out of the center.”

— — -

War as sacrifice

At the same time, the bloody and violent logic of the archaic warrior’s world continued to figuratively shape the the kshatriya’s worldview and inform his conduct on the battlefield— that greatest of sacrificial altars. In the epic imagination (the closest to the divine warring bloodlust of the archaic rajans), the king’s sacrificial festival was hypertrophised as the epic ‘sacrifice of battle’ (ranayajna). In the Mahabharata’s Shanti Parva, Indra speaks of the samgrama-yajna ‘war-sacrifice’:

The chunks of the enemy’s flesh are the offerings; their blood is the clarified butter…. The blood which runs upon the earth from the violence of war is its full libation.

(tr. Fitzgerald, 1973)

Nicolle (2022) writes of the medieval world’s acceptance of the ‘inevitability of conflict,’ of how “the kshatriya caste’s abhorrence of dying in bed rather than on the battlefield [resulted in] chronic warfare.” The Rajputs conceived of battle as “a sacrificial fire into which oblations in the form of dead soldiers were thrown.” (Roy, 2012)

The warrior who succumbed in battle was assured fame, glory, ‘fame that does not decay,’ as well as celestial pleasures and luxuries; descriptions of celestial apsaras descending onto the battlefield, enamored by the fighting heroes, eager to marry them, is a common trope in medieval Indic literature. War itself is a form of worship, a grand sacrificial rite, a profoundly spiritual enterprise. ਕਹੂੰ ਜੰਗ ਕੇ ਰੰਗ ਕੇ ਰੰਗ ਪੇਖੇ॥—Somewhere you are seen in the ecstatic colors of battle.

This is the essence of the kshatriya’s dharam: ecstatic, bloody, triumphant destruction at the vigorous peak of one’s martial and physiological prowess in the womb of the Devi’s warring vortex. To fall not in the haze of infirmities, but in the over-great fullness of life.

Bataille (1957) writes, “A violent death disrupts the creature’s discontinuity”, revealing primordial continuity in a moment of ecstatic, profound rupture. ਭਿਰੇ ਸਾਮੁਹੇ ਮੋਖ ਦਾਤੀ ਅਭੰਗੀ ॥—He who falls before you [the Devi, the sword] is granted salvation, O unbreakable one.

ਸਾਮੁਹਿ ਪ੍ਰਾਨ ਦੇਤ ਜੋ ਜਾਈ ॥ ਸੋ ਪਾਵਨ ਸੁਰ ਪੁਰ ਬੜਿਆਈ ॥—He who confronts [the enemy in battle] and gives his life, he attains a passage to the pure land of the gods. The pure land of the gods— Indra’s celestial sabhaa, Odin’s hall, the Guru’s sachkhanda darbar.

ਸੋ ਖਾਲਸਾ ਪੰਥ ਭੀ ਦੇਵਤਿਆਂ ਦਾ ਪੰਥ ਚਲਾ ਆਇਆ ਹੈ।—So the order of the Khalsa has always been the order of the gods.

— — -

yathā piṇde tathā brahmāṇde

यथा पिण्डे तथा ब्रह्माण्डे।—As is the body (microcosm), so is the universe (macrocosm). Corbin’s ‘law of correspondence’ posits that “there is homology between the events taking place in the outer world and the inner events of the soul” (1971). By extension, the kshatriya’s worldly principle of catastrophe finds a homology in the inner world of intensities and impulses that informs Klossowski’s reading of Nietzsche.

In the Dasam Grantha’s Rudra Avatara, Guru Gobind Singh presents the turmoil of psychic processes as an eternal battle between the armies of ਬਿਬੇਕ (bibek—wisdom, discernment) and ਅਬਿਬੇਕ (abibek—ignorance). Their armies are numbered by multiple warriors (each personifying aspects of one’s inner life: qualities, drives, impulses, moods, temperaments, virtues, vices) such as ਕਲੇਸ਼ (conflict), ਆਲਸ (sloth), ਭਰਮ (doubt), ਮਦ (wine), ਵਿਯੋਗ (separation), ਵਿਗਿਆਨ (science), ਜੋਗ (meditation), and so on. ਖਪ੍ਯੋ ਸਰਬ ਲੋਕੰ ਅਲੋਕੰ ਅਪਾਰੰ ॥—[The war] transpired across all lokas (cosmic realms), manifest and occulted, over the course of ਬੀਸ ਲਛ ਜੁਗ—two million yugas.

In his Gay Science, Nietzsche rejects the intellect as “something conciliatory, just and good”; instead, he sees it as the ‘battlefield’ of ‘warring impulses.’ The act of comprehending merely a precarious armistice between obscure, vigorous forces resolving itself in ‘sudden and violent exhaustion’—akin to the kshatriya’s self-destructing, catastrophic principle of conflict. Klossowski writes:

Moreover, conscious thought—especially the thought of the philosopher—is most often the expression of a fall, a depression provoked by a terrible quarrel between two or three contradictory impulses that results in something unjust in itself.

Similarly, in a katha Giani Harbhajan Singh Dhudhikey speaks of the gods living within the Gursikh’s body: Indra in the arms, Agni in the glow of the face, Narayan in the conscious, and so on. In a note to Klossowski’s essay ‘Nietzsche, Polytheism and Parody,’ Ford brings up the idea of “psychic dispositions as divinities; antagonistic and conciliatory dispositions as divinities given to quarrelling and coupling,” presupposing “a notion of space where the inner life of the soul and the life of the cosmos form a single space.”

The battles of the asuras and the devas, the inner life of warring intensities, the kshatriya’s catastrophic world of crisis, the Devi’s wrath—reflections of the same cosmic ਦੰਗਾ. यथा पिण्डे तथा ब्रह्माण्डे।

— — -

The inner world of pathos

Klossowski contrasts conscious thought—goal-directed, gregarious, social, projecting itself forward (teleological)— with the unconscious life of impulses and intensities, which is beyond the structures of logos. The greatest pleasure of the pathos, the unconscious, is to be without a goal. A freely dissipating realm of joyous, ecstatic, solar ruin and expenditure.

Here, eternal metaphysical ‘truths’ turn out to be simply the impulse that best intensifies life’s will to power, the one that overcomes and subjugates other agonistic impulses. This is the perpetual movement of the universe, which Nietzsche’s Zarathustra sees as

the dance of gods and the prankishness of gods, and the world seemed free and frolicsome and as if fleeing back to itself—as an eternal fleeing and seeking each other again of many gods, as the happy controverting of each other, conversing again with each other, and converging again of many gods.

Questions of morality hold no water here because the impulses function beyond the structures (and strictures) of conscious thought (Najm Kobra’s black light cannot be seen for it is the cause of seeing). What rises up to ‘conscious thought’ is merely the aftermath of this great struggle. So it is that the will to truth is transvaluated, in Nietzsche’s view, into a life-preserving error.

The apparatus of the consciousness— of the Self— reins in and orients this boundless unconscious in service of its telos, forming an image of them as goal-seeking. Forced into this structure, “the impulses are alienated from their own image for the benefit of the goal.” As the Rudra Avatara concludes its tale, it is written that ਬਿਬੇਕ and ਅਬਿਬੇਕ, and the army of miscellaneous impulses that fight with them, ਇਨ ਜੀਤੇ ਜੀਤੋ ਸੰਸਾਰਾ ॥—In mastering them, one wins the world.

In effect, this mastering reflects the unifying principle of dharam, of civilization, of logos, ‘the Self, the World, and God’— stemming from the same conceptual mechanism meant to harness, organize and unify the violent, warring, libidinal conflict of impulses into a coherent, stable, ordered, productive economy— intensity into intention, chaos into cosmos, ਦੰਗਾ (riot, chaos) into ਧਰਮ (dharam, cosmic order).

Much like the priest’s stable order emerges from the cosmogonic violence of sacrifice, the joyous violence of unconscious intensities is reined in through violence.

— — -

This paradigmatic framework— simultaneously arbitrary and profoundly essential, precarious and permanent— corresponds to the solar anchor of dharam reining in the Devi’s wrath, of man’s technics utilizing Shakti, of unity subsuming multiplicity, of civilization conquering nature. This is, all in all, the maneuver that captures and orders the all-devouring, freely hemorrhaging vortex provoked by the Devi’s wrath, in perpetually fluctuating, alternating cycles.

The tension between this formless energy and the framework of dharam is reflected in what Klossowski calls the incoherence of intensity (impulses, drives) and the coherence of intention (the self).

Existence seeks a physiognomy in order to reveal itself... What reveals existence? A possible physiognomy: perhaps that of a god.

(Klossowski, 1957)

Dharam (as articulation and expression of doctrine) must not be understood as a post hoc conceptual strategum that arrives after the act to fabulate and interpret the free play of intensities into a meaningful cosmos (in which case it would be one among many antagonistic impulses); but as an intervention from above by necessary, immutable order (logos, the law, the Father) that inaugurates the cosmos: divinely conditioned form, making sacred time accessible, sustaining a symbolic realm through which one can cross the worldly ocean and ascend towards the sun-door.

ਭਈ ਪਰਾਪਤਿ ਮਾਨੁਖ ਦੇਹੁਰੀਆ ॥ ਗੋਬਿੰਦ ਮਿਲਣ ਕੀ ਇਹ ਤੇਰੀ ਬਰੀਆ ॥—This human form has been bestowed on you. This is your chance to meet Gobind.

This is repeated over and over, for the order of dharam is incomprehensible (even inhuman, inaccessible, and so, overwhelmingly impossible) until it is revealed via hierophanic ruptures (the arrival of avataras, the revelation of scripture)— arriving time and again as cycles of control give way to chaos.

(At the same time, this very articulation dooms itself, for in entering the conscious it becomes articulable and hence communicable, gregarious, subject to manipulation, decay and corruption. And yet it is this same fallen state that creates the possibility of redemption and, in its departure from dharam, reveals its necessity. Hence the endless flow of the yuga cycles, each defined by an intervention.)

— — -

In each case— God, the World and the Self— a competently upheld structure continues to extract and utilize formless, chaotic, potent reserves of energy; the system is sustained by battling the entropy inherent to any system of control and establishing an equilibrium, attaining a self-regulating organicity— Spengler’s culture tipping into civilization. As long as this paradigm is upheld (redeemed), it staves off the cataclysmic fulfilment of the kshatriya’s principle of conflict.

To competently maintain and make use of this superabundant energy— held in constantly reinforced equilibrium, for the Devi’s wrath continues to seek its dissipation in the form of a self-devouring vortex of violence, to revert to the rapturous dance of warring intensities— is akin to the cowboy astride a bucking bull, the matador fluttering and dancing around the charging bull, tempting death— a task that demands virtue (in the classical sense).

Such a one is the deathless initiate, the consecrated warrior infused simultaneously with the solar light of dharam and the chaotic wrath of Bhagauti; the Man of Light (the Grail winner, the soma thief, fellow of the gods). After all, “Liberation is for the Gods, not for men.”

In less capable hands, as the structures begin to crumble, this precariously maintained arrangement is upended and ਦੰਗਾ commences— the kshatriya’s principle unleashed in all its sublime, terrifying, apocalyptic fury, until order is restored (or ‘reimposed’).

And so the cycle continues: this is the metabolics of the yuga cycle (an idea that must be set aside for now, to be tackled later).

— — -

The Devi’s cherished hunting ground

A nihilistic, chaotic ultraviolence has always stalked the land of Punjab, lurking its hamlets and forests and dusty tracts. Folk heroes and rebels such as Jeona Morh, Dulla Bhatti, Maula Jatt, all the way to the violent, fabled lives of modern-day gangsters like Bindy Johal, all attest to the prominence of violence as a principle in Punjabi society.

Amidst the vicissitudes of history’s mesh of recurrences, the principle of conflict that drove the archaic Vedic tribes to war continued to saturate the soil of Punjab with blood.

Punjab, it seemed, was the Devi’s favorite territory, her cherished hunting ground, her altar of sacrificial violence. Provoking tribal conflicts, blood feuds and religious wars, she continued to revel in the heavy aroma of casual, brutal violence that drifts from the wilderness of Punjab’s history; continued to bask in the heat of battle, filling her bowls with the blood of fearless Aryan thugs. And the insolent, hardy, bellicose people of Punjab continued to serve as her worthy wine-bearers.

— — -

The solar nature of the Khalsa’s violence

The Khalsa reined this violence in and harnessed it in service of its will-to-power: the endemic violence of feuds and vengeance elevated to the pursuit of patishahi, to waging chaoskampf, to the struggle for satiyuga. The destructive savagery and petty logic of feuds and vendettas was transfigured through the solar conduit of dharam into creative, sacred violence, laying the grounds for the sacred time of satiyuga, enabling a “movement from emitted formlessness to ritually created structure.” (Smith, 1989)

If the ‘feminine’ can be axiomatically coded as chaos, formless, ‘hysteria’, darkness, acquisition, and the ‘masculine’ as order, form, differentiation, solarity, self-sufficiency, then the Khalsa is what ennobled and elevated Punjab’s nihilistic violence to the stature of dharam-yuddha.

The Guru was ਮਰਦ ਅਗੰਮੜਾ—the man without parallel/without equal, and he who abides by the Guru’s code must be ਮਰਦ ਕਾ ਚੇਲਾ—disciple of a man, ਮਰਦ carrying connotations of manliness and martial prowess.

This nihilistic violence, still very much a part of the Khalsa’s foundation, is alchemically transfigured by the brilliant light of the Guru’s dharam (the alchemical agents here being ਨਾਮੁ—Divine Name, and ਅੰਮ੍ਰਿਤ—Nectar of immortality, administered during initiation into the Khalsa).

— — -

As divine faculty (Corbin: “that which cannot itself be seen, because it is the cause of seeing”), an uncreated, infinite, inaccessible general economy of luxuriating intensities, the Devi is endless potential and power— a plenitude that is accessible in its totality only by the solar Man of Light, the Master of Maya, the supreme Lord himself.

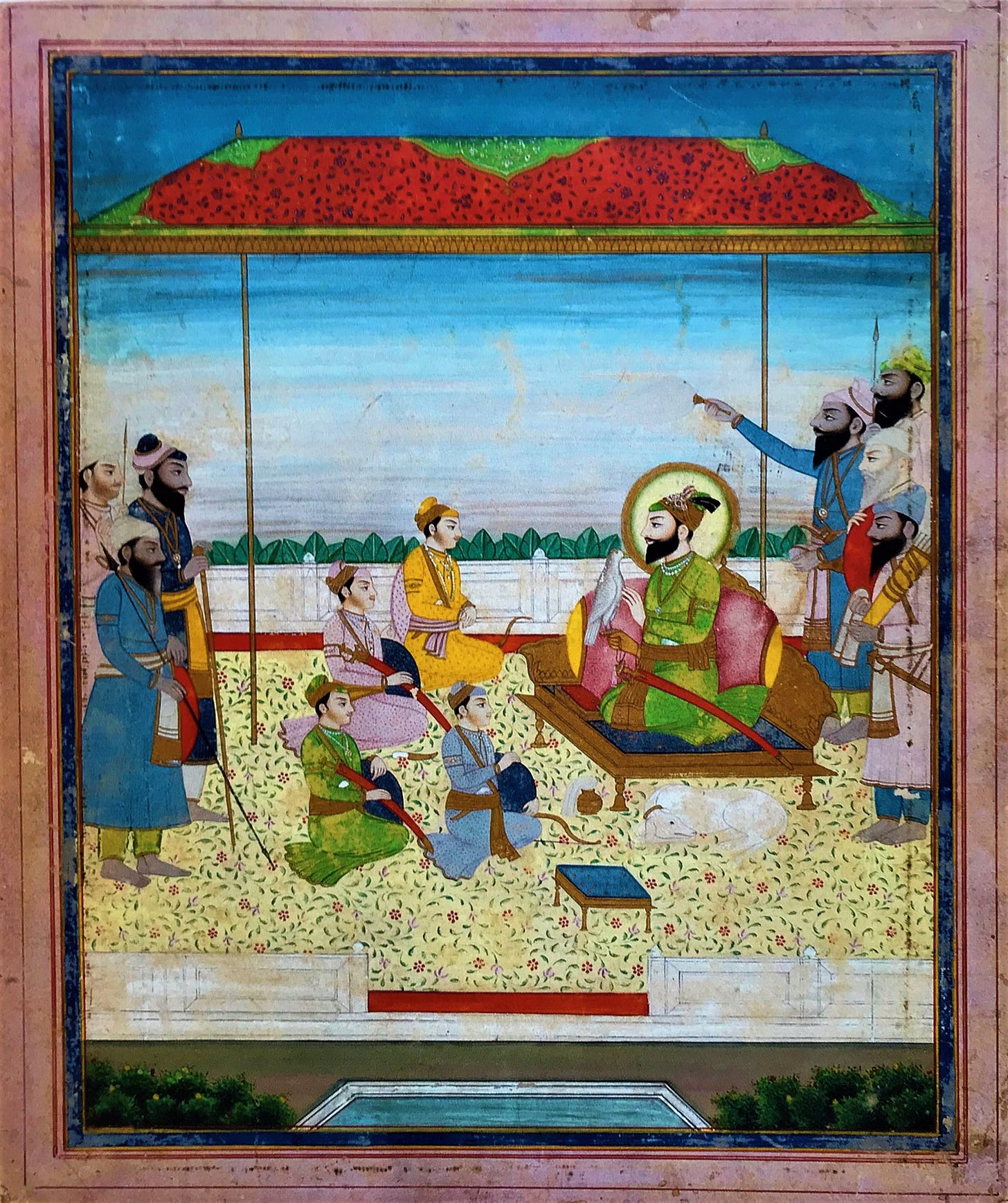

Guru Gobind Singh Maharaj, King of Kings, the Solar All-Father, conjured the Devi ‘ਅਪਣੇ ਸਰੂਪ ਵਿਚੋਂ—from within his own form’ (Vahiria), and infused her splendorous might in the Khalsa. Warre gods of the solar dynasty, the Khalsa is not only noble but ennobling: in elevating the wretched to grace, the meek to power, the wicked to virtue, the Khalsa represents the true standard of nobility.

In the depths of the kaliyuga, the Guru entrusted the Khalsa with a beautiful, tantalizing contradiction: that of making use of the gunas, vikaras, elements, tonalities that constitute the Devi’s domain while waging war against the wrathful, luxuriant wilderness of chaos and violence she engenders (the Devi as phenomenal flux, chaos).

Heesterman (1993): “the kṣatriya is given to inauspicious activities, eating improper food, killing, and plundering.” ਪੋਸਤ ਭੰਗ ਅਫੀਮ ਸ਼ਰਾਬੈਂ । ਝਟਕ ਬੱਕਰੇ ਛਕੈਂ ਕਬਾਬੈ ।—[Consuming] poppy, cannabis, opium and alcohol, [the Singhs] would behead goats and eat kebabs. ਬੀਸ ਪਚਾਸ ਸਿੰਘ ਮਿਲ ਜਾਵੈਂ । ਇਤ ਉਤ ਤੈ ਗ੍ਰਾਮਨ ਲੁਟ ਲ੍ਯਾਵੈਂ ।—Whenever twenty or fifty Singhs would gather, they would roam around fearlessly plundering villages.

Dumézil (1969) notes that Indra and his warriors must possess qualities similar to the forces they fight against:

they must first possess and entertain qualities of their own which bear a strong resemblance to the blemishes of their adversaries. In battle itself they must respond to boldness, surprise, pretense, and treachery with operations of the same style, only more effective, or else face sure defeat. Drunk or exalted, they must put themselves into a state of nervous tension, of muscular and mental preparedness, multiplying and amplifying their powers. And so they are transfigured, made strangers in the society they protect.

Waging chaoskampf against the kaliyuga by making use of its own resources: “the unification of multiplicity, by means that belong to the world of multiplicity itself.” (Guénon, 1930) The Nietzschean striving for ‘a maximal feeling of power; essentially a striving for more power’. Affirming the unifying principle of God, the World and the Self, by assenting to and overcoming the luxuriating plurality of intensities. Descending into the heart of darkness; becoming ਦੰਗਾ to conquer ਦੰਗਾ.

— — -

For the Singhs have been initiated into the mysteries: having given their heads to the Guru, having attained the mystical unity of all life; having passed through the sun-door and returned as differentiated, sovereign sirdars; their will “completely absorbed in an existence rendered to itself”, they draw their sovereignty from the godhead of the Guru.

Cloaked in the blue of Shiva-Rudra and the Iranian mystics (kabud-pushan), they are meant to thrive in the realm of Maya as householder-sovereigns, as ਭੋਗੀ-ਬੈਰਾਗੀ (hedonists-ascetics), at ease with the ways of the world and yet utterly divested from it; negotiating the demimonde nomos of the night with the supreme Light of lights in their heart-lotus; carrying the halahala of worldly struggle and turmoil in their throats, even as their hearts are awash with the amrita of pure, resplendent light.

Indifferent to life, disdainful of death; immortal and yet dying every moment, over and over, an endless procession of ascendant becomings; ਬਸਤ੍ਰ ਸ਼ਸਤ੍ਰ ਭੂਖਨ ਸੋਂ ਬਨੇ ।—Dressed in fine clothes, weapons and jewelry, and yet ਬਿਦੇਹੀ—without a body, ਅਕਾਲੀ—deathless, beyond time/death, their faces turned forever towards the eternal Guru.

— — -

Having died in life (jeevan-mukta), what remains is the fulfilment of the warrior’s principle: to be torn apart in the heart of the Devi’s vortex. This is what the warrior orients his entire life towards, this is what he longs for and knows, knows in the heated blood surging beneath the tautness of his skin, in the preternatural reflexes and vigilance of his senses, in his clarity of vision, in the marriage of limb and weapon, mind and hand, in the vigorous, explosive flexion of muscles.

ਦੰਗਾ— this is the fundamental impulse that drives the kshatriya, the impulse that emerges victorious and wills the totality of one’s being towards its dissipation. And if psychic dispositions correspond to divinities, the kshatriya’s impulse finds its highest representation in the Devi’s vortex of war. It would not be inappropriate to recall Pandit Nihal Singh’s remark that the Khalsa in its most ferocious form embodies tamoguna: the chthonic, Dionysian, consumptive elements of death, darkness and chaos; berserker rage, pure, devastating aktion— ਦੰਗਾ.

— — -

The Khalsa weds the warrior’s principle of catastrophic violence with the unifying principle of dharam, the Devi’s black light with the solar radiance of dharam, without decentering the warrior from the center of the dharmic world. In the ever-circling gyres of history, the archaic Vedic rajan’s bloody, ecstatic lust for war— what Eliade (1954) calls ‘the state of sacred fury (wut, menos, furor) of the primordial world’— bloomed afresh in the temporal birth of the Khalsa (metaphysically, the Khalsa is eternal). ਛਤ੍ਰੀ ਕੋ ਪੂਤ ਹੌ ਬਾਮਨ ਕੋ ਨਹਿ—I am the son of the kshatriya, not the brahmin.

As the stable, transcendental order of the ritualists is swallowed up by the turbulent, apocalyptic volatility of the kaliyuga’s coda, the Khalsa’s defense of dharam, of rta, of cosmic order, must stem from a reaffirmation of the kshatriya’s practice of war within this world, blood, guts and all— rather than the hieratic sphere of perfect ritual, detached and transcendental. War is recentered as the fount of divinity: the warrior its high priest, the swing of the sword (the burst of the gun, the barrage of artillery) its highest spiritual modality.

Dumézil remarks on Indra’s disregard or defiance as yathavasam, “according to his own will”: the law unto himself, he is alone and he is free. The Singh, as a consecrated warrior, himself embodies the dyad of jurist-priest and magician-king; the Singh is a complete man. Strength expresses itself as strength.

— — -

The Devi’s general economy

The Panth Prakasa speaks of how in every yuga, the Devi was appeased by the worthy warriors of dharam for assistance: the gods led by Indra in the satiyuga, Sri Rama in the tretayuga, the Pandavas in the duaparyuga. In the kaliyuga, it was the Guru who conjured the Devi and obtained this ferocious vector of war, conditioning it with dharam (whether dharam is natural law or moral-ethical code is a broader conversation about civilization and nature, beyond the purview of this note).

Bhangu further weaves together tales of Prithviraj Chauhan, Hazrat Muhammad and Banda Bahadur invoking the Devi (in the form of the apocalyptic Kali) to fulfil their endeavors, only to succumb to her wrath. The Devi’s capricious, cataclysmic vortex of war, once unshackled, rapidly grows volatile and chaotic, ultimately consuming everything. ਜੋਊ ਜਗਾਵੈ ਰਜਾਵੈ ਨਾਂਹਿ। ਵਹਿ ਭੀ ਉਸਕੋ ਛੋਡੈ ਨਾਹਿਂ।—He who awakens her but fails to propitiate her [appetite], she too doesn’t spare him [her wrath].

This is the general economy of the Devi’s intoxicated, libidinal, vigorous, superabundant wealth of energy, a formless expanse that seethes and roils without a goal; a realm of ruinous expenditure unto itself, a cosmic ocean of supraconscious chaos and vitality, exulting in the relentless churn of creation, production and destruction, without aim, without end. ਦੰਗਾ. The ancient battles of the gods, the bloodiest industrial war, the derangement of the senses: children playing in the mother’s lap. “… beyond the (cerebral) intellect there lies an intellect that is infinitely more vast than the one that merges with our consciousness.” (Klossowski, 1969)

Within this cosmic economy, this ravenous, destructive force demands sacrifice. He who conjures it is fated to be devoured by the very force he invokes for divine assistance, manifesting it in its purest form through total war. This is the cruel, cold heart of the kshatriya’s heroic, fatal sacrality, “the ever-recurring sacrificial hour of death.”

— — -

ਜਿਸ ਦਿਨ ਤੇ ਚੰਡੀ ਜਗਵਾਈ। ਚੰਡੀ ਕੋਪ ਕਰ ਉਲਟੀ ਆਈ।—From the day [the Guru] had awakened the goddess Chandi, she had turned her wrath on him. In awakening the Devi’s wrath, the Guru also sounded the bugle for the Khalsa to wage relentless dharam-yuddha, to step into the eye of the vortex and triumphantly master it.

From here on there would be nothing but ਦੰਗਾ: chaos, war, riot, destruction. This is the kshatriya’s principle of conflict. This is the Devi’s vortex of war. This is the true caste and clan of the Singhs. (Do you see? Do you understand?)

— — -

Having conjured Akaal’s shakti in the form of the Devi and infused her light in the Khalsa, the Guru too honored the Devi’s cosmic economy, offering his own blood in return for the Devi’s potency: the four saahibzaade, his four sons, fulfilled this transaction, attaining the exalted peaks of martyrdom in defense of dharam.

Insofar as the son is the father’s very incarnation, insofar as the sacrificer identifies with the sacrifice, it was his own self that the Guru offered to the Devi. Indeed, in symbolically immolating his sovereign spiritual-temporal authority and joining the order of the Khalsa as a Singh, the Guru had already metaphysically fulfilled his self-sacrifice.

In turn, the Khalsa, having already sacrificed their heads to the Guru, sons of Mata Sahib Devan, court martyrdom in service of dharam and fill the Devi’s bowl. ਇਤਨੇ ਮਰੇ ਜੁ ਸ਼ਸਤ੍ਰਨ ਨਾਰ। ਤੌ ਕਾਲੀ ਕੋ ਪੁਜੂ ਅਹਾਰ।—After so many [Singhs] have died, only then will Kaalee’s appetite be propitiated. The martyr’s sacrifice upholds the principle of dharam while also fulfilling the Devi’s appetite. True nobility expends and gives away freely, profusely, gloriously.

As the Khalsa’s temporal reign manifests and crumbles endlessly in the vicissitudes of historical time, the idea of satiyuga effectively becomes fungible: bursts of sacred white heat destined to wilt and perish time and again in kaliyuga’s multiplicitous reign of quantity. The Khalsa must die over and over to uphold dharam. The martyr’s death holds the cosmos in place.

— — -

As long as the Khalsa abides by the Guru’s rehit, and lives as his very image, as pluralities of the Guru (who in turn is form of God himself), this volatile, fatal violence, obtained and sustained through the vicious turmoil of history, is controlled and marshalled in service of dharam. It is only in upholding the noble (Arya) solar path of the Gurus that the Khalsa’s violence is ennobled; the inner path towards the sun-door and the worldly path towards patishahi are the same.

The sword of God’s wrath generates no karam of its own, for its actions are divinely mandated— for the wills and egos of these deathless warriors, in essence, participate in the highest Will and Ego (the unifying principle of Brahm, -੧- ਏਕੜਾ), and derive their sanction from it. Every righteous act of the Khalsa is vindicated in the court of Mahaakaala.

As the custodians of dharam in the kaliyuga, the Khalsa masterfully contains and makes use of the Devi’s sublime wrath, wielding it in the form of the sword. It must burn in the fires of the Devi’s wrath (even as it remains immersed in Akaal’s light), become simultaneously intensity and intention, aware that it is betrothed to death, fated to perish in the Devi’s vortex of war at the peak of their power, triumphant.

ਮਰਣਾ ਮਰਣਾ ਮਾਰਿ ਮਾਰਿ ਗਲਣਾ ਗਲ ਗਲ ਸੀਤ ਸਰਬ ਖਾਲਸਾ ਤਿਆਗ ਤਨ ਤਾਂ ਲਗ ਸਹੀਦਨ ਰੀਤ।—We shall kill and be killed. We shall be dissolved in heaps of ice as high as man's stature. All the Khalsa will then throw off their bodies and shall obtain the dignity of martyrs.

— — -